The Season Begins

One More Thing? Ha!

I have one more important task to do before planting any vegetables this spring, and that is the annual mapping out of the garden, something I generally put off as long as possible.

In theory, mapping out my garden should be easy. I “rotate” what I plant in each bed so that no vegetable, or any of its relatives, grows in a given bed more frequently than every 3 years.  In practice, I mostly pay attention to rotation of plants most susceptible to diseases, which are cabbage and its kin (all in the Brassicaceae), cucumber and its kin (Cucurbitaceae), tomato and its kin (Solanaceae), beans and peas (Fabaceae), and corn (sweet or pop, in the Gramineae).

In practice, I mostly pay attention to rotation of plants most susceptible to diseases, which are cabbage and its kin (all in the Brassicaceae), cucumber and its kin (Cucurbitaceae), tomato and its kin (Solanaceae), beans and peas (Fabaceae), and corn (sweet or pop, in the Gramineae).

Crop rotation prevents buildup of disease pests that overwinter in the ground; removing host plants eventually starves them out. (Insect pest are more mobile, so crop rotation has less impact except in very large plantings.) So one year a bed might be home to cucumbers, melons or squashes. The next year that bed might host cabbage, broccoli, kale, Brussels sprouts, or cauliflower. Then tomatoes, peppers, potatoes, or eggplants. And finally, the fourth year, back to cucumbers. Simple enough.

It would also be nice to rotate carrots and other root vegetables with leafy vegetables, such as lettuce, and fruiting vegetables, such as tomatoes.  Root, leafy, and fruiting vegetables have somewhat different nutrient needs, so in the ideal garden these crops are rotated to make best use of soil nutrients.

Root, leafy, and fruiting vegetables have somewhat different nutrient needs, so in the ideal garden these crops are rotated to make best use of soil nutrients.

And I do like to get the most out of my garden and confuse potential insect pests by grouping different kinds of plants within a bed.

Are you beginning to understand why I put off committing my garden plan to paper each spring?

Pea Problem(s)

Peas present one more wrinkle in my vegetable garden planning. A few years ago they stopped bearing well, collapsing with yellowing foliage not long after they bore their first pods.

A few years ago they stopped bearing well, collapsing with yellowing foliage not long after they bore their first pods.

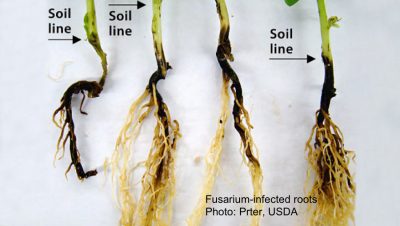

Further investigation has narrowed the problem to – probably – one of two diseases: fusarium or aphanomyces. Both, unfortunately, are long-lived in the soil so that a 3 year rotation does nothing to keep them in check.

Fortunately, I have two vegetable gardens. So, for the past few years I have banned peas from my north garden, planting them only in my south garden, in which they do get rotated. After a few more years, I’ll move the pea show to my north garden and leave my south garden pea-less. I’ve also been planting the varieties Green Arrow and Little Marvel, both of which are resistant to fusarium, at least.

Unfortunately, the problem is more likely aphanomyces, for which resistant varieties do not exist. Aphanomyces is a water mold, so thrives under wet conditions. So my tack will also be to keep any peas planted in my vegetable garden on the dry side, not even turning on the drip irrigation in those beds.

I’ll also be checking the plants more closely for symptoms. Plants infected by fusarium have a red discoloration to their roots.  Plants infected by aphanomyces have fewer branch roots and what roots there are lack the plump, white appearance of healthy roots.

Plants infected by aphanomyces have fewer branch roots and what roots there are lack the plump, white appearance of healthy roots.

Pea Solution?

I’m also testing out root drenches with compost tea for my peas.

Yes, yes, I know I have dissed compost tea in the past. Mostly, its benefits, if any, have been overstated. But compost microbes have more chance of surviving in the dark, moist, nutrient-rich environment of the soil than on a leaf, where the stuff is often sprayed. I’m drenching the soil with the tea, not just giving the surface a spray, as usually recommended, so a lot more bacteria, fungi and friends are finding their way down there.

I see no reason (and research does not support) of going to the trouble of making the usual compost tea, which is aerated and might be fortified with such things as molasses.  My tea is nothing more than the liquid strained from compost soaked in water, then applied with a watering can at the base of the pea plants.

My tea is nothing more than the liquid strained from compost soaked in water, then applied with a watering can at the base of the pea plants.

I’ve done this for a couple of seasons but have nothing definite to report yet. The hard part is sacrificing a bed as a control. Perhaps this year.

Ruth Stout had it right. “Feed them (the worms) and they will come”.

Yup. Same with soil microbes. Another reason for annually enriching a soil with organic materials. Aerated compost tea sprays, as I’ve written many times, do little to inoculate a soil with beneficial microbes — just feed the soil and they will come. (My compost tea drench may be another story because this is more than a light surface spray. It temporarily floods the soil. And the soil is anyway rich in organic matter — 15%, the result of annual additions of compost and no-till.)

Comforting to know I’m not the only one who puts off this task. I am just finishing the planting plans for the 25 or so clients I serve. The spring crunch has me wishing I had done this in December! Very grateful for your perspective on rotation. My method has been to focus solely on rotating nightshades, as I was most familiar with the risk of their soilborne diseases. The advantage of this approach is that it simplifies things (being intentional about rotating just one crop type versus thinking about all the crop groups you mentioned). Fortunately my clients always elect to have the full permissible one-third of their garden planted with nightshades, so when I rotate that one-third, every other plant has to move to a new spot as well, so the rotation of all groups typically happens anyway.

You gave me advice on a fig last spring – a Chicago Hardy that mostly died through the winter, and the client was upset. I’m happy to report that the fig produced a couple fruits (flowers) at the end of the season, and I protected it with a salt hay enclosure this winter to great effect – it’s healthy and alive from trunk to tip!

Thanks for all you do, and happy spring!

Glad to be of help.

Chicago Hardy is, I believe, no hardier than many other figs. Roots of figs often survive even cold winters but if a fig dies back too much, there’s not enough time for it regrow and ripen any figs.

Lee,

Big eggplant problems this year despite a banner year last year. Leaves are turning brown and shriveling up and the plants do certainly look like the’re dying. I haven’t been able to find any photos of eggplant diseases that resemble what’s happening to my plants. I remember you writing about a particular blight that commonly affects eggplants in our area. Is there anything to be done to save the plants this year?

The biggest problem with eggplants is flea beetles, whose damage is nothing like what you describe. Could this year’s symptoms be from too much or too little water, or too much chemical fertilizer?