GOOD FUNGI, BAD WEEDS

Myco . . . What?

There’s a fungus among us. Actually, fungi, all over the place. Right now, though, I’m focussed on a special group of fungi, a group that, as I look out the window on my garden, the meadow, and the forest, has infected almost every plant I see. Like so many microorganisms — most, in fact — these fungi are beneficial.

The fungi are called mycorrhizal fungi; they have a symbiotic relationship with plants. (“Mycorrhizae” comes from the Greek “myco,” meaning fungus, and “rhiza,” meaning root.) The plant and the fungus have an agreement: The plant offers the fungus carbohydrates which it makes from sunlight, carbon dioxide, and water; in exchange, the fungus infects plant roots and then spreads the other ends of its thread-like hyphae throughout the soil to act to be virtual extensions of the roots. The plant ends up garnering more mineral nutrients from the soil. The fungus also helps offer protection against pests and drought. It’s an arrangement that has worked for eons.

Except for where soil has been doused with heavy doses of pesticides or discombobulated by land excavation, mycorrhizae are everywhere. Only a few plant families get along without this symbiosis. Some more familiar, nonmycorrhizal plants include cabbage and its kin, carnations, lamb’s-quarters, and sedums. Other plants can grow without mycorrhizae, but then miss out on some of the benefits and don’t make most efficient use of minerals soil has to offer.

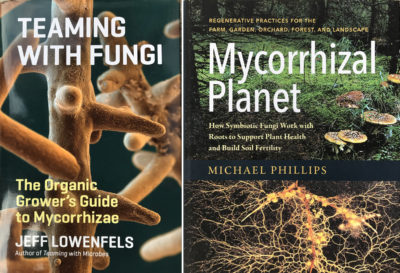

Why mention mycorrhiza at this moment of time? Two books on mycorrhiza were published this year; either one, but not both, are worth reading. Both cover the kinds of mycorrhizae, their effects, their nurturing, and probably everything else you might want to know about this symbiosis.

Michael Phillips’ Mycorrhizal Planet will appeal more to the hip gardener, the one who burns wood for biochar for their soil, builds hugelkultur mounds (look it up), and spritzes plants with herbal extracts to boost their immune function. He’s mostly right when writing about mycorrhizae but often enters the land of woo-woo when venturing off-track. For instance, he writes, and then runs with, “many species of insects lack the digestive enzymes needed to break down complete proteins.” Not true.

The other book about mycorrhizae, Jeff Lowenfels’ Teaming with Fungi, presents a similar overview to mycorrhizal fungi, and their application, to that presented in Mycorrhizal Planet, with one notable difference. Teaming with Fungi details straightforward methods how you or I can actually grow our own mycorrhizae with which to inoculate plants to get them off to the best possible start.

The two books differ dramatically in their writing style. I eventually tired of Phillips’ overly flowery style and anthropomorphizing. “The synergy that unfolds as a result of outrageous diversity in the orchard delights me to no end . . . .The root systems of fast-growing tree with relatively pliable wood make barter possible between AM [arbuscular mycorrhize] and EM [ectomycorrhizae] fungi.” Lowenfels’ Teaming with Fungi is more firmly grounded in real science and application than Mycorrhizal Planet. I found Lowenfels’ writing more straightforward and engaging: “Some trees form AM, but others have evolved over time and are hosts to EM. Some trees are hosts to both forms of mycorrhizae, though usually at different periods in their lives.” (Different strokes for different folks.)

The mycorrhizal symbiosis was first studied and described in the latter half of the 19th century. Less long ago, but still long ago, I studied them as part of my doctoral work, specifically the ericoid mycorrhizae that are specific to blueberry plants and their kin. With the increased appreciation of the diversity, extent, and effect of the living world within the soil in recent years, mycorrhizae have moved into the spotlight. Read about them, nurture them, and make use of them.

And Weeds Among Us

Rising now to see what’s going on aboveground, I see that the garden has moved mostly into its maintenance phase for the season. That entails mowing, scything, making compost, keeping an eye out for pests and taking action, if necessary.

And, of course, weeding. My weeding weapons of choice are my hands, for larger interlopers, and either the winged weeder hoe or wire hoe for small ones. Called into action weekly, either of the two hoes easily slice through the top quarter inch of soil surface to do in small weeds that haven’t even yet poked their heads above ground.  All the better to forestall the appearance of large weeds, which are much harder to kill and also threaten to spread seeds or grow strong roots. Regular hoeing also keeps the soil surface loose to better absorb rainfall.

All the better to forestall the appearance of large weeds, which are much harder to kill and also threaten to spread seeds or grow strong roots. Regular hoeing also keeps the soil surface loose to better absorb rainfall.

Early July seems to be when true gardeners part ways with other gardeners. Regular weeding and other garden maintenance keeps the garden in good shape for the fall garden which, with good maintenance and planning, is like having a whole other garden, providing vegetables and flowers well into fall.

It’s a tribute to the tenacity of weeds how they manage to take root or sprout, and then thrive, in the small openings between adjacent bricks. Even in the small cracks between the bricks and the masonry wall of the house. Some of those “weeds” are actually welcome there — such as the wild columbines that send up thin stalks at the ends of which hover orange and yellow blossoms whose rear-pointing spurs gives the flowers the appearance of flaming rockets.

It’s a tribute to the tenacity of weeds how they manage to take root or sprout, and then thrive, in the small openings between adjacent bricks. Even in the small cracks between the bricks and the masonry wall of the house. Some of those “weeds” are actually welcome there — such as the wild columbines that send up thin stalks at the ends of which hover orange and yellow blossoms whose rear-pointing spurs gives the flowers the appearance of flaming rockets.