MORE THAN JUST PEACHES AND PLUMS HERE

Preiselbeere, Kokemomo, Puolukka, Partridgeberry, Cowberry, Rock cranberry — or Lingonberry, They’re All the Same Fruit.

Besides enjoying the season’s plums and peaches, I’m also enjoying a few uncommon fruits. Uncommon now. These fruits have been enjoyed by humans somewhere at sometime, just not extensively now.

The most familiar of these to most would be lingonberries (Vaccinium vitis-ideae). As jam, in jars, that is, unless you’re Scandinavian, where this fruit is very popular harvested from the wild and then used in drinks, sauces, and pancakes.

Lingonberry, which is native throughout colder regions of the northern hemisphere, is often compared with our native cranberry. I think that does lingonberry an injustice. Both are diminutive plants, spreading as their stems root where they touch the ground, so could be edible groundcovers. Both are evergreen, but while lingonberry’s dainty leaves have the same green gloss as those of holly, and retain it all winter, cranberry leaves turn a muddy purple with the onset of cold weather in late fall.

I recently read that the berries are “not good to eat in their raw state as they are quite bitter.” That writer evidently never tasted lingonberries; I eat them raw all the time and find them delicious. And it’s not because my taste buds are so robust. I’d never pop a cranberry, which is closely related to lingonberry, into my mouth. Too, too sour.

Lingonberry is now ripening fruits — and it’s also blossoming! The plants bloom twice each season, yielding an early and a later crop.  If not harvested, the later crop hangs, looking pretty and in good condition for eating, through autumn and on into winter.

If not harvested, the later crop hangs, looking pretty and in good condition for eating, through autumn and on into winter.

To thrive, the plant needs similar conditions to those enjoyed by blueberry, cranberry, mountain laurel, rhododendron, and other lingonberry relatives. In addition to good drainage and abundant humus, the soil needs to be very acidic, with a pH ideally between 4.5 and 5.5.

Right after planting and then each year thereafter, some time between fall and spring, my lingonberries get mulched with a one- to two-inch depth of some finely divided, organic material that is not too rich in nutrients: sawdust, woodchips, chopped straw, or shredded leaves, for example. The mulch sifts down through the leaves and stems to keep the ground cool and moist, prevent frost from heaving plants in winter, and decompose to maintain high humus levels in the soil — all of which translates to larger berries and more of them.

The plants require little care beyond regular watering for the first couple of seasons.

Centuries of Flavor

Also ripe now is a fruit that has been enjoyed by humankind for the past seven thousand years (although not so much now)! At a site in northern Greece, early Neolithic peoples left traces of their meals of cornelian cherry (Cornus mas), along with remains of einkorn wheat, barley, lentils, and peas. It was also well-known to the ancient Greeks and Romans. The hard wood was reputedly the wood for chariot axles.

The plant was grown in monastery gardens of continental Europe through the Middle Ages and was introduced to Britain about the sixteenth century. By the eighteenth century, the plant was common in English gardens, where it was grown for its fruits which sometimes were called cornel plums.

The fruit was familiar enough to be found in European markets even up to the end of the nineteenth century. Cornelian cherries were especially popular in France and Germany, and the fruit reputedly was a favorite with children.

Native to regions of eastern Europe and western Asia, the cornelian cherry is still appreciated for its fruit in certain parts of these regions. Baskets of kizilcik, as the Turks call the fruit, are found in markets of Istanbul. The fruit is a popular backyard tree in gardens of Moldavia, Caucasia, Crimea, and the Ukraine.

When the fruit was popular in Britain, it was made into delicious tarts, and shops commonly sold rob de cornis, a thickened, sweet syrup of cornelian cherry fruits. The juice also added pizazz to cider and perry.

Depending on ripeness, fruit flavor varies from sweet to tart. It has a distinctive flavor and can be used in cookery at all stages. If tart fruit is allowed to sit for a day or two or three, the flavor becomes less tart and more mellow.

Cornelian cherry is a favored ingredient of Turkish serbert, a fruit drink sold in stores and from portable containers carried like knapsacks on the backs of street vendors. In the Ukraine, cornelian cherries are juiced, then bottled commercially into soft drinks. There, the fruits also are made into conserves, fermented into wine, distilled into a liqueur, and dried.

The plant is actually not a true cherry, but a species of dogwood. It is still widely, but mostly planted as an ornamental for its very early show of small, yellow blossoms, around the first day of spring here on the farmden.

Cornelian cherry is among my most successful fruit crops. Despite its early bloom, it has never failed to bear. Birds, insects, and diseases have little effect on production. Pruning is unnecessary. What else can you ask for from a fruit plant?

(I am still looking for some good recipes that use this fruit and lingonberry for possible inclusion in an update of my book Uncommon Fruits for Every Garden. Got something? Both fruits are covered in my currently available books, Landscaping with Fruit and Grow Fruit Naturally.)

Intoxicatingly Delicious?

This last fruit is very uncommon, and I didn’t plant the tree mostly for its fruit. Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis) bark is gray with corky ridges that, especially in winter when illuminated by low-hanging sunlight, has that crisp, achromatic quality of photographs of the lunar landscape.

Hackberry bark

The fruit itself is refreshingly sweet, like a date. Problem is that the fruit is pea sized and contains an almost-pea-sized seed. So the fruits nothing more than a thin covering over the seed.

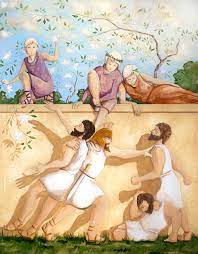

More prominent in the human diet is a close relative, one name of which is the lote tree (C. australis), which even figure in Greek mythology. When Zeuss drove Odysseus’ ships off course, the sailors finally found refuge in the Island of the Lote Eaters. Eating the fruits caused a pleasant drowsiness, to the extent that the sailors, forgetting their homes and friends, wished for nothing more than idling away on the island. Odysseus had to drag them back onto their ships.

The lote tree, native to Europe and temperate regions of Asia, is pretty cold-hardy (Zone 5). I have ordered seeds and should get to taste fruit of the lote tree in a few years. I might never leave the farmden.